Everything you need to know about asbestos

Asbestos is a heat-resistant fibrous mineral that naturally occurs in the ground. For nearly 150 years, it was widely used to create fireproofing, insulating, and soundproofing products.

Six different minerals can be described as ‘asbestos’ and are all known carcinogens, though the three main types used in Britain were chrysotile, amosite, and crocidolite. Their prolific use in the construction, textile, automotive, and shipbuilding industries means that, even though asbestos was officially banned in 1999, the danger to British citizens’ health is ongoing.

Chrysotile (white asbestos)

Chrysotile, or white asbestos, was the most common type of asbestos manufactured around the world. Despite being the last type of asbestos to be banned in the UK in 1999, it can still be found in large quantities today.

Where was chrysotile asbestos used?

Over the decades, chrysotile was used in many hundreds of household items, and found its way into most residences and industrial buildings.

Since its fibres are fine and soft in nature, it was often woven and spun into asbestos textiles like fireproof blankets, safety clothing, and even theatre curtains.

The substance was used for acoustic and fireproofing purposes, especially for flooring and wallboards in densely-populated areas and industrial centres alike. Chrysotile was also used by the automotive industry to make brake linings, clutches, brake pads and gaskets

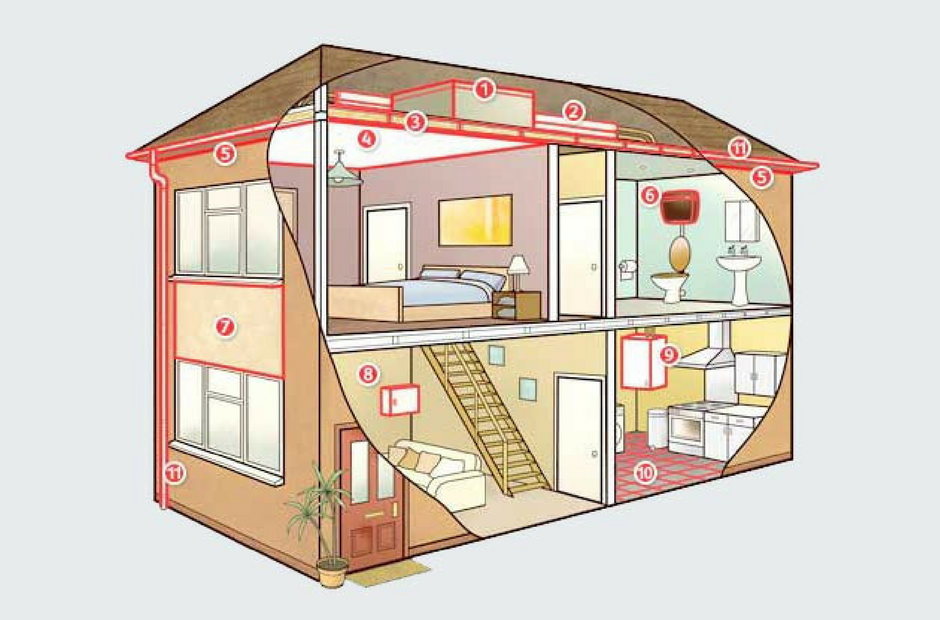

Where can you find chrysotile asbestos in the UK today?

- Water tanks

- Asbestos cement

- Asbestos insulation boarding

- Ceiling and floor tiles

- Partition walling

- Pipes

- Gaskets

- Fire blankets

- Gutters and downpipes

- Soffits

- Roofing sheets

- Roofing shingles

What is the difference between serpentine and amphiboles asbestos?

Chrysotile belongs to the serpentine family, and its fibres are softer and curvier than their cousins in the amphibole group. Their flexibility made it extremely easy to develop a myriad of products like fabrics, insulation, and much more. It is said that, if inhaled, chrysotile fibres are more readily expelled by the body than amphiboles, with a needle-like composition.

Amphiboles fibres can easily penetrate lung walls when breathed in, and offer a serious risk to health when airborne.

No matter the variety, however, all asbestos dust and fibres pose a serious health risk, and are the cause of many illnesses including pleural mesothelioma and asbestosis.

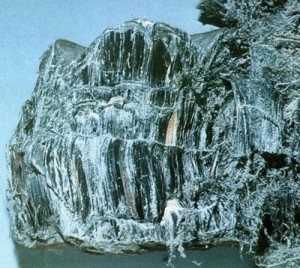

Crocidolite (blue asbestos)

Also known as blue asbestos, crocidolite is a fibrous form of the mineral Riebeckite. Mined in South Africa, Australia, and Bolivia until the 1960s, it is widely believed to present the highest risk factor for any form of asbestos due to its high ‘friability’ rate. This means that fibres break up easily when disturbed.

Blue asbestos was renowned for its fire-retardant and insulating properties, and – with the strength of its fibres – became a widely-used resource across many industries. Construction, automotive shipbuilding, and even the tobacco industry used the substance on a regular basis (Lorillard Tobacco patented its crocidolite-containing Micronite filter promoting it as a healthy alternative to standard cigarette filters of the day!).

Banned in the UK in 1985, crocidolite’s particularly strong needle-like fibres lodge in the lung linings when inhaled.

Amosite (brown asbestos)

‘Amosite’, or brown asbestos, is actually an acronym and trade name for grunerite, a member of the amphibole group of minerals. It was largely mined in the Transvaal Province in South Africa, which is where the name originated – Asbestos Mines of South Africa (AMOSA).

Amosite offers great resistance to heat and has strong insulating properties. For these reasons, it was a common addition to construction materials in many countries around the world. Its long, brittle fibres are easily broken, however, and readily inhaled. It is regarded as the second most dangerous type of asbestos, and was banned in the UK in 1986.

Where is amosite found today?

This dangerous substance still remains in many of our older buildings, posing a danger to workers and members of the public undertaking DIY, refurbishment, renovation, and demolition work.

Building products requiring high-tensile strength were often manufactured using amosite. These included:

- Roofing tiles

- Ceiling and floor tiles

- Cement sheets

- Electrical insulation

- Pipe lagging

- Chemical insulation

- Asbestos insulating board

Because of their excellent fire resistance, ceiling tiles containing amosite were commonly used in educational buildings, and have been the subject of debate for many years.

Other forms of asbestos

Though these three forms of asbestos may have been used less prolifically than chrysotile, crocidolite, and amosite, they still pose a significant danger to health if their asbestos dust or fibres inhaled.

Tremolite

Tremolite was commonly a part of other minerals including vermiculite, talc, and chrysotile asbestos. Tremolite can occur in shades of green, grey, white, and brown.

Mined in only a few places globally (and in small amounts), products containing the substance are not often seen in this country. However, it is thought to be as dangerous as other forms of asbestos if handled incorrectly.

It may be found in:

- Asbestos insulating board (AIB)

- Asbestos cement sheeting and pipes

- Casings for telecoms and electrical wiring

- Thermal insulation, such as lagging

- Fire doors

- Gaskets

- Vermiculite products such as loft insulation, whitewashes and packaging materials

- Talc products, including ceramics and chalks

- Paint and sealant

Anthophyllite

Anthophyllite is a magnesium and iron silicate that is fibrous in nature, and also extremely brittle. It is generally brown in colour, but may include shades of green, grey, and yellow. Unlike crocidolite and amosite, anthophyllite fibres have low tensile strength did not have a high value in the asbestos industry.

Anthophyllite is naturally found in various areas of America, Asia, and Northern Europe – Finland in particular.

It can be found in the vermiculite products and, historically, in cosmetic talcum powders. Due to its insulating and fireproofing properties, anthophyllite asbestos may also be found in:

- Asbestos cement

- Composite flooring

- Insulation

- Roofing material

- Paints and sealants

Actinolite

Actinolite is similar in nature to tremolite, but far less commonly used. It was mined in several areas around the world, including Australia and the United States (North Carolina).

This substance was often included in insulation and fireproofing materials, along with other minerals, and is generally brown, grey, or green in colour. Older residential and commercial buildings may still contain products manufactured with actinolite, as it provided a lightweight insulating solution in the building trade.

Its other uses also included:

- Concrete materials

- Sealants and paints

- Horticultural vermiculite

Mesothelioma and other asbestos-related diseases

If inhaled or ingested by the body, all forms of asbestos have the potential to cause life-threatening disease. The long latency period of asbestos disease means that people may not be aware they have an asbestos-related illness for several decades – sometimes up to 60 years from the initial exposure. Shockingly, up to 5,000 citizens die each year from exposure to asbestos.

Mesothelioma

When asbestos dust and fibres are breathed in, they settle within the lining of the lungs, setting up the environment within the body that causes this untreatable type of cancer. Mesothelioma begins to aggressively attacks the outer lining of the lungs, and after diagnosis, life expectancy is typically no longer than 18 months.

Although there are three types of the disease, the most common form is pleural mesothelioma.

Asbestosis

Asbestosis is a long-term illness that results in severe breathing problems due to scarring on the lungs. Although non-malignant and varying in severity, it is thought that asbestosis is often a precursor to mesothelioma.

Asbestos-related lung cancer

It can be difficult to attribute lung cancer purely to asbestos exposure, as the disease manifests in the same way as other types of lung cancer (such as that caused by smoking). Asbestos-related lung cancer generally begins between 20 and 30 years following exposure to the substance, but can progress considerably quicker if the sufferer is also a smoker.

Does asbestos always pose a danger?

If left undisturbed, asbestos is not considered a specific danger to health. It is only when attempts are made to remove it – or when its fibres and dust are released into the air – that it becomes a health hazard.

Many people are unaware of the risks posed by asbestos – it is commonly thought that it was a historical problem, rather than a current one.

Who is at risk from asbestos exposure?

Anyone whose work could bring them into contact with asbestos is potentially at risk.

Private individuals renovating their own properties may also be at risk, but due to the increased likelihood of tradespeople coming into contact with asbestos, they are the group most often exposed to these harmful substances. These include tradespeople such as plumbers, heating engineers, and electricians, but also surveyors, architects, and engineers.

Taking a wider viewpoint, it is possible that anyone working within commercial or public buildings such as schools and hospitals, could also be unwittingly exposed to asbestos dust and fibres. The prevalence of asbestos-containing materials (ACMs) within the construction industry – even in sites’ rubble and soil – extends the threat further.

So where might asbestos be found within these buildings?

How to stay safe if you encounter asbestos

The Health and Safety Executive has issued specific guidelines regarding the handling of asbestos. If any company is found not to have followed these requirements, they face prosecution, unlimited fines, and potential prison sentences for the individuals involved.

Anyone untrained in the safe removal of asbestos is not only risking their own health, but also the safety of those around them should it be disturbed. If workers unexpectedly encounter a substance they suspect to be asbestos, they must leave it undisturbed. When in doubt, always make the assumption that it is, in fact, asbestos.

A risk assessment should then be carried out. If necessary, licensed contractors may be called in to deal with higher-risk ACMs such as sprayed coatings, insulation, and lagging. If a licensed contractor is not required, only those specifically trained in non-licensable work should carry out the removal process.

Whose duty is it to manage asbestos?

The Control of Asbestos Regulations 2012 (CAR12) state that the duty to manage asbestos lies with the owners or occupiers of commercial buildings who are in charge of maintenance and repair. Landlords also have a duty to manage asbestos in ‘common’ areas such as lifts, staircases, boiler rooms, store rooms, and outbuildings.

An asbestos survey should be carried out to identify where asbestos is located within the building. A risk register can then be used to record its presence, condition, and whereabouts, being updated regularly to provide a current view of the exposure risk.

Complete asbestos awareness training for compliance and safety

Every British employer must provide asbestos education to all employees who may come into contact with ACMs. Asbestos awareness training covers all six forms of asbestos, so you’ll learn where they might be found, what they look like, and what the proper protocol for handling a situation is.

At Bainbridge E-learning, we offer the most competitive rates for UKATA online asbestos awareness courses. Contact us today!

UKATA registered Asbestos Awareness online training

Contact us

If you have any questions about the course, please contact us via the Contact page.

You can also reach us by email at support@bainbridgeelearning.co.uk or by phone on 01843 260580.

We’re based at

Aylesbury

Bucks

HP20 1DA

About Asbestos

Heading

Asbestos Queries

For any questions regarding the content of this course, please call 07772 557635